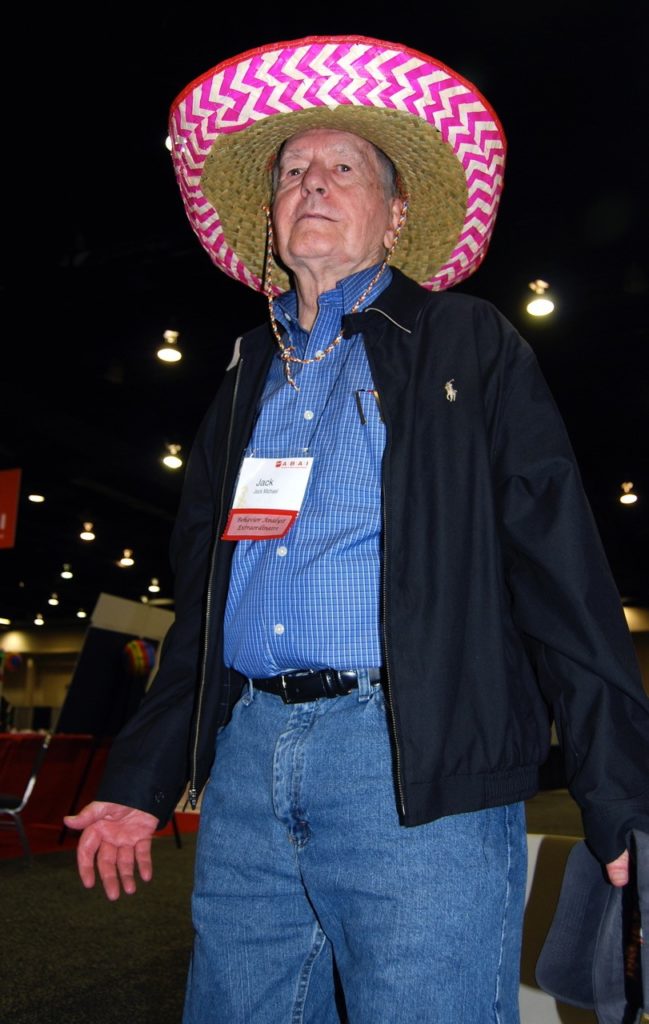

A Personal Tribute to Jack Michael’s Influence

by Bruce Hesse and Hank Schlinger

One of the pioneers of our field, Jack Michael, died on November 12, 2020. It would be difficult indeed to overestimate the influence Jack had on the field of behavior analysis. For example, most everyone knows about his significant contributions to our understanding of verbal behavior and his elegant analyses of conceptual issues. It is probably not widely known, however, that Jack could be considered the father of applied behavior analysis (ABA).

His article with his student Ted Allyon, “The psychiatric nurse as a behavioral engineer” (1959), is arguably the first published article in applied behavior analysis, and epitomized what Jack and his friend and colleague at the University of Houston and Arizona State University, Lee Meyerson, referred to as rehabilitation. Today, of course, what Jack and Lee and their colleagues did would be called applied behavior analysis (ABA).

It would also be difficult to overestimate the influence Jack had on the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI). Jack was there from the beginning when the Midwestern Association for Behavior Analysis (MABA) was founded, and he proceeded to play a role as a member of the Organizational Committee that established the first meeting of MABA (Peterson, 1978). Of course, MABA later became the Association for Behavior Analysis and then the Association for Behavior Analysis International. In addition to his many contributions to ABAI, Jack served as its president in 1979.

In addition to his contributions to the experimental, theoretical, and applied analysis of behavior, Jack mentored and advised numerous students beginning in the late 1950s and continuing until his retirement in 2003. Many of his students themselves have become luminaries in the field and have contributed significantly to the three branches of behavior analysis in their own right, mentoring and advising students, thus keeping the behavior analytic lineage passed on by Jack alive.

Interestingly, befitting a pioneer in any field, tributes to Jack appeared long before his death. For example, Mark Sundberg published an appreciation of Jack’s contributions to the analysis of verbal behavior (Sundberg, 2017), and John Mabry offered his reflections as one of Jack’s first students on Jack’s faculty positions at the Universities of Houston and Arizona (Mabry, 2016). Barb and John Esch (2016) published an extensive bibliographic tribute to Jack in terms of the influence his work had had up to that point. Hank Schlinger and Dave Palmer (two of the recipients of the Jack Michael Outstanding Contributions in Verbal Behavior Award) offered their own tributes to Jack and his influence on their lives and careers as behavior analysts in the 2016 edition of the VB News (Palmer, 2016; Schlinger, 2016).

Upon his death, Hank Schlinger and Mark Sundberg were asked to be action editors for tributes to Jack that will appear in upcoming issues of The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. The first issue will include tributes by some of Jack’s early students, and the second issue will contain tributes from some of his more recent students and colleagues. Moreover, both the Operants and VB News are planning their own tributes.

In this tribute for Inside Behavior Analysis, we, who were two of Jack’s many students and mentees, talk about our personal experiences with Jack as our advisor and mentor and how he influenced and changed our lives and careers.

Before either of us even thought about pursuing graduate study in behavior analysis, we had read books by Skinner, which convinced us that there was a way to a better future. At that time, the Psychology Department at Western Michigan University (WMU) was one of the programs that offered a wide variety of courses and practical experiences in behavior analysis. It provided a unique environment for students to study and experience Skinner’s radical behaviorism in action. At WMU, graduate students were aligned with various faculty members who worked to advance and refine the details of behavior analysis. We were lucky enough to be aligned with Jack.

Jack was well known for the quality and rigor of his classes and for his understanding not only of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior, but the whole range of behavior-analytic research and theory. Jack’s courses included an EAB class in which students read articles from the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (JEAB) on topics in basic research with nonhumans, his famous verbal behavior class, a class on the philosophy of radical behaviorism, and a class on the application of behavior principles to college instruction. As new students with no formal academic training in the complexities of behavior analysis, coming into this environment evoked a lot of self-doubt. Studying with Jack changed all of that. He had spent most of his academic life immersed in behavior analysis. Following in the footsteps of Skinner (1968) and Keller (1968), he recognized the value of applying behavior analysis to teaching at the college level. It was clear that the philosophy that guided his teaching was the philosophy that brought us to this graduate program. After one successful semester of Jack’s classes, we knew we made the right choice.

Jack arranged the contingencies in his classes as if he were conducting a thematic line of research on complex human verbal behavior in a behavioral science laboratory; and the learning went both ways because over the years the students’ performances shaped Jack’s behavior of tweaking the courses. A course plan was developed, and the specific assignments were given. The students’ developing verbal repertoires were frequently sampled, adjustments were made based on weekly student outcomes, and the cycle continued throughout the semester. Jack never stopped refining his methods based on outcomes. Study objectives were improved with each iteration of a class. Exams were almost always short answer with answer keys provided before the next class period. Exam questions were different each semester and usually constructed during the instructional week they were used. With the help of his TA, Jack also did most of the grading. His doctoral teaching assistants were apprentices, picking up tasks that matched their developing skills.

Having experienced these classes first as a student and then as a teaching assistant, it is no surprise that we, and many of Jack’s students, were drawn to university teaching. Those years with Jack taught us the value of good teaching, how much work goes into creating a productive learning environment, and how long-lasting the effects of that environment can be.

Following Skinner’s example, Jack sought to clarify how we talk about some complex topics using our behavioral terminology and methodology. During the period when researchers were debating the linguistic competence of nonhumans (apes and parrots), Jack started using more pigeon analogues as thought experiments in his Verbal Behavior class. These thought experiments soon became the impetus for creating a prototype pigeon lab where students used minimal equipment (a pigeon on a table with some handheld stimuli) to investigate some of Skinner’s verbal operants (Michael, Whitley & Hesse, 1983). It was a great, low-cost teaching tool to get students actively involved in problem solving using behavioral principles and terminology. Later, we built a more traditional pigeon lab involving computer-controlled operant chambers to investigate some of the topics Jack talked about in his classes.

Currently, at California State University, Stanislaus, students in the experimental analysis of behavior classes can learn shaping skills with a pigeon on a table, modeling what was done in Jack’s lab. This class is one of the most popular undergraduate teaching labs in the psychology major that attracts students to graduate study in behavior analysis. It also is used to investigate master’s-level thesis research questions using computer-controlled equipment. During the time that one of us directed the graduate ABA program at California State University, Los Angeles, there was an experimental analysis of behavior course in which students read JEAB articles, a radical behaviorism course, and, naturally, a course on Skinner’s Verbal Behavior.

For those of us who were inspired by Skinner’s views on how a science of behavior could be applied to everything in the human and nonhuman animal world, Jack was our example. When he taught graduate classes in the early evenings, students were sometimes less alert in class. Rather than blaming the students, Jack considered the contingencies. Every class had an exam over the week’s material. If the exams were given after the lecture, students spent less time participating in the lecture and more time reviewing their notes for the upcoming exam. When Jack moved the exam to the beginning of class, students still did not participate in the lecture because they were checking their notes with what they remembered writing on the exam. The problem was solved with a simple environmental adjustment. As the students finished writing their exams, they would meet outside Jack’s office. The teaching assistant was there with a cart containing hot water for instant coffee (there was no Starbucks then) and tea plus some healthy snacks and the exam answer key. Students snacked together and talked about their study experiences and what they thought of the exam; this became part of the learning environment. At the end of this break, they returned to class refreshed, and primed (with a little coaching from the teaching assistant) to participate in lecture. Often what this meant was asking Jack to clarify things they thought they understood but did not based on his answer key. The behavior change plan worked, and Jack got what he wanted, an evening class with students actively participating each week.

Jack was a modest person. He explained his many contributions in terms of the verbal environments from which they evolved. Jack attracted bright and highly motivated students through his teaching. He was genuinely interested in their developing repertoires and how they would contribute to advancing behavior analysis. He also recognized the positive influence these students had on his own theoretical work and writing. This could come from student comments in class, individual out-of-class conversations, topic-based group meetings (Sunday mornings with Father Jack as Mark Sundberg has said) or social events.

Jack always noted interesting observations of complex human behavior and offered plausible radical behavioral explanations. He supported his explanations with carefully crafted examples based on research data and/or convincing metaphors. For him, behavior analysis was more than the data reported in a behavioral research journal; it was a way to approach everything having to do with behavior.

When Fred Keller died in 1996, Jack remembered him as follows: “Fred had still another kind of influence, perhaps for many his most important. He was a model for many essential professional and personal qualities” (Michael, 1996, p. 5). He went on to list the qualities related to teaching, public presentations, accepting awards, wry humor, not taking oneself too seriously, and being warm with others. Clearly these were important to Jack. Of the many things we learned from him over the years, we also consider his most important influence to be the way he modeled the same professional and personal qualities.